“I think I want to do a Big Year…kinda.” I said to Jeannette.

“You want to do WHAT? You? Why?” she responded.

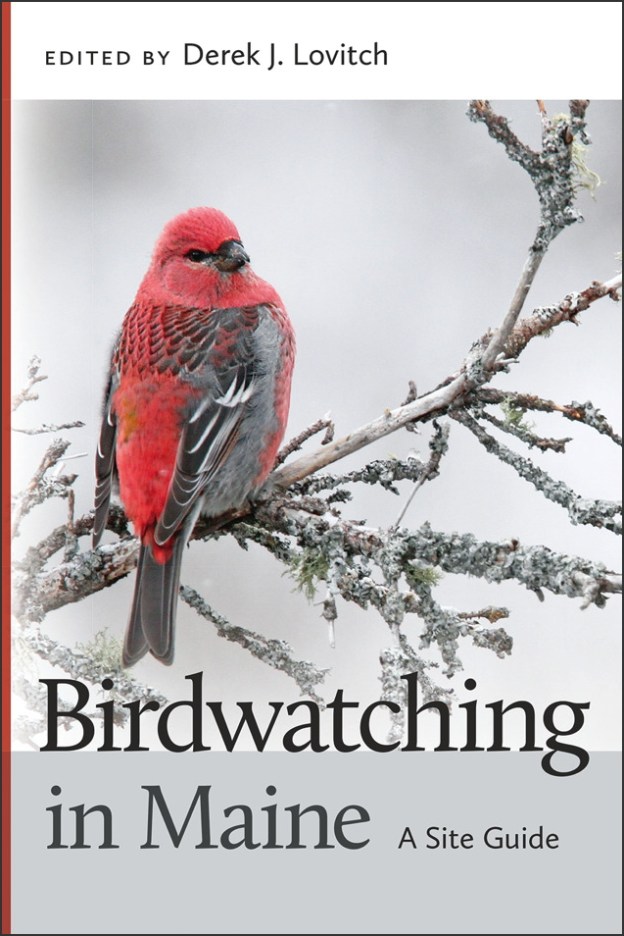

Several friends I floated the idea to had similar initial responses. But when I explained my concept, they started to understand, and be supportive. It wouldn’t be a regular Big Year where I ran around willy-nilly chasing after everything that was reported. Instead, it would have a very specific parameter: I would only count birds – and for that matter, only seek birds – at places covered in my book, Birdwatching in Maine: A Site Guide published this past spring by the University Press of New England.

The goal was to “ground-truth” the comprehensive-ness of the book. Did I successfully cover all of the breeding species? What about the best migrant traps? Rarity Hotspots? Could birding only with this book result in a respectable year list? I set a goal of 300 species in the year in order to act as “proof of concept.”

So off I went.

There were some very good rarities around in January, so the year list got off to a great start. An overwintering immature male and female King Eider in Portland Harbor (Site C5) were nice additions, as you can never really count on where one will be in any given year.

The Mid-Coast was particularly hot and Jeannette and I caught up with the two Pink-footed Geese at the Samoset Resort (Site KX5) on 1/30…

…and the Mew Gull at Owl’s Head Harbor (Site KX4) on the next day

Alas, the Bullock’s Oriole – only the second state record – was at a private feeder in Camden most of the winter, but could not be counted on my little endeavor. But January also produced some good winter irruptives that I would not see in the fall of 2017, such as Pine Grosbeak and Bohemian Waxwing. Of course, since Pine Grosbeak is on the cover, I couldn’t miss that one!

While February is generally a slow month for rarities, a few good year list additions included a Short-eared Owl at Reid State Park (Site SA3) on February 2nd – a bird I chased (but would find a couple in the fall), and then a lucky find of a Dovekie on Valentine’s Day that Jeannette and I enjoyed from The Cliff House (Site Y4).

Slow growth of the list continued in March, but I was seeing most of what was expected. A Canvasback at Fortunes Rocks Beach (Y11) was a quick twitch on 3/20. As migration picked up in April, it was time to get to work. I spent much of my month at our Bradbury Mountain Spring Hawkwatch (Site C18), especially on days with conditions that have produced rarities in the past.

Fly-by Sandhill Cranes on 4/3 would save me some effort later in the year…

…and I was excited to spot a Black Vulture on April 11th. The vulture, however, paled in comparison to the Bird of the Day: a fly-by Townsend’s Solitaire! (my first self-found in Maine).

By month’s end, Neotropical Migrants began to return, but an impressive storm system at month’s end looked prime for “southern overshoots,” so I dedicated as much time as I could to migrant traps along the coast. The Biddeford Pool neighborhood (Site Y12) is always my first destination in such circumstances, but I did not expect a Gray-cheeked Thrush there on 4/27. My first in spring in Maine, this was a far more satisfying addition than a nocturnal flight call or fleeting glimpse in the fall!

My southerly expectations were met on Bailey Island (Site C23) the next day, where I found my first White-eyed Vireo of the year…

…and my first of what would be a total of four self-found Hooded Warblers on the year. I synthesized the weather and birding from this storm in a blog entry.

The list grew with each day in May – thanks especially to my local patch, Florida Lake Park (C20) – occasionally punctuated by an important addition, such as the Evening Grosbeaks that flew over Old Town House Park (Site C16) during my Saturday Morning Birdwalk on the 20th. I caught up with the only annually-occurring Orchard Orioles in the state at Capisic Pond Park (Site C9) on the following day.

My guiding schedule was jam-packed in 2017, and tours would take me all over the state as usual. It began in May with a single day tour in Rangeley on the 18th, which produced Mourning Warbler and Gray Jay, among other “first of years” in the boreal forest.

Then, as usual, it was off to Monhegan Island (Site L1) with the store’s tour group for Memorial Day Weekend. Any visit to Monhegan during migration offers high hopes for rarities, and with a total of three tours there this year, I needed it to produce for me. However, despite a really great and birding weekend, I came away with “only” Summer Tanager…

…and a very-rare-in-spring Orange-crowned Warbler (but I would find a total of five in the fall).

My 10-day tour comprehensive breeding season tour for WINGS is especially important for me to clean up the breeding birds, such as this Spruce Grouse at Boot Head Preserve (Site WN8) on 6/21.

During that tour, the waters between Maine and Machias Seal Island (Site WN7) delivered Common Murre and more Razorbills and Atlantic Puffins (my first puffins of the year on the boat to Monhegan in late May).

Usually in June, I am too busy to chase (rarities are always on the opposite side of the state than I am during any given tour), and once again, I missed a few goodies (we’ll get to those in a little bit). However, I always had an incredible stroke of luck with not just two great rarities in two days, but two State Birds for me in two days that I happened to be free for. Or, actually, mostly free.

One June 12th, our wedding anniversary, we were getting ready to head to our fancy dinner in Portland when we received word of a Magnificent Frigatebird over Prout’s Neck in Scarborough. We hurried, raced to Pine Point (Site C1), called the restaurant which graciously allowed us to delay our reservation, and spotted the frigatebird in the distance, soaring over Prout’s Neck.

The next day, we had plans with our new neighbors, Meghan and Mike Metzger. We were supposed to head over to their house for cocktails in the evening, but when word of a Snowy Plover – a first state record! – at Reid State Park (Site SA3) was received, we decided to test the new friendship. “So, what do you guys think about maybe a walk on the beach on this sultry (record warm, actually) evening?” We figured any friends of birders would eventually find out what it’s like to be friends of birders, so we might as well break them in early. And now that their first life bird was a Snowy Plover in Maine, perhaps we’ll make birders out of them someday.

With a few red-letter rarities and good luck with many of the regular breeding birds in Maine, I finished my June insanity (I was in the store a total of four days all month!) with 258 species after Jeannette and I paid a visit to the King Rail pair breeding once again along Eldridge Road at Moody Point (Site Y5). Glancing over the checklist, I realized that with some dedicated effort, this Big Year-esque project could turn into something.

Therefore, in July, Jeannette and I made sure to use our “weekends” together to fill in the holes on the year list. Every 4th of July weekend, we visit with Bicknell’s Thrushes, and this year was no different. Hiking up Sugarloaf Mountain (Site F12) on the 3rd added the species to my Maine year list (my June tours all go to New Hampshire for this much sought-after species).

The following week, we went up to the Baxter State Park area. A wildly productive first full day in the area (7/10) yielded the Black-backed Woodpecker that had so far eluded me this year, as well as the extremely rare American Three-toed Woodpecker, along Harvester Road (Site PS6) and at the Nesowadnahunk Campground Road (Site PS7), respectively. White-winged Crossbills were everywhere too (as were Reds). Unfortunately, Jeannette’s camera was on the fritz, and documentation eluded us.

Phil McCormack and I make an evening visit to the Kennebunk Plains (Site Y9) for Eastern Whip-poor-will every summer, and this year’s outing on 7/8 added that to the list. The list kept growing.

The Little Egret returned to the Falmouth-Portland waterfront for its 3rd summer, and although it was a little more elusive this year, I spotted it from Gilsland Farm (Site C8) on July 14th.

Without a Birding By Schooner tour this summer, I needed to make up a few pelagic ticks, the first of which were Manx Shearwaters that I spotted from East Point (Site Y12) in Biddeford Pool on my birthday, 7/31, with Pat Moynahan, John Lorenc, and Terez Fraser.

From August through early October, I took several boat trips – basically whenever I had the chance and conditions were decent. The Cap n’ Fish Whale Watch (Site L3) out of Boothbay Harbor was very good to me this year, yielded all of the regularly-occurring shearwaters, Parasitic Jaegers (here, on 8/11, but my first of the year were spotted at Dyer Point – Site C3 – on 7/25)…

And some more Manx Shearwaters from the same date

And a whopping 28 Pomarine Jaegers on October 10th.

One huge void from not doing a schooner trip this summer was filled on August 6th when I spotted “Troppy”, the Red-billed Tropicbird at Seal Island (Site KX6 and H1) that has returned for its incredible 11th year. I accepted an offer to fill in as boat naturalist for a friend who was doing a couple of the Isle au Haut Ferry’s special “Puffins and Lighthouses” evening tours this year. I said yes for the chance to not miss out on a visit to Seal Island for the year…or for my year list. Thanks, Laura Kennedy!

A few other serendipitous twitches and finds in August really helped out my quest. There was the Black-necked Stilt that was found at Weskeag Marsh (Site KX2) on August 2nd. We happened to be away on North Haven for the night before, so this was an easy 1-mile diversion on our way home that afternoon!

I missed White-faced Ibis in Scarborough Marsh this spring, and all summer it was only being seen in and around Spurwink Marsh in Cape Elizabeth, which is not technically a site in the book. Therefore, I was ecstatic to find it back in Scarborough Marsh while I was searching for shorebirds along the Eastern Road Trail (Site C1) on August 7TH.

That day was big for me, as it also added Baird’s Sandpiper…

…and Stilt Sandpiper to my list.

My first Western Sandpiper of the year came from there as well, on August 21st.

Our summer vacation this year took us out of the state once again, this time to New Brunswick and the Bay of Fundy for the Semipalmated Sandpiper migration spectacle. But our roadtrip finished up at Campobello Island, where we crossed the border for the day to visit our friend Chris Bartlett in Eastport (Site WN13) for a boat ride into the wildly productive waters of Passamaquoddy Bay and Head Harbor Passage on August 20th. Luckily, we found the Little Gull in Maine waters…

…as well as my first Red-necked Phalaropes of the year.

Heading into the Big Year project, I was hoping a few of the book signings I would do around the state would give me the chance to add a couple of new species to the list, chase a bird or two I wouldn’t have driven as far for, or otherwise just check out a few sites that I rarely if ever bird. A talk and signing in Bar Harbor on September 7th gave me the chance to find a Blue Grosbeak behind the Mount Desert High School (Site H6) before my program. Little did I know at the time, but this would be my only sighting of the year, so this was another really lucky find.

It doesn’t take a Big Year to get me to Sandy Point on Cousin’s Island in Yarmouth (Site C14) at every possible opportunity to take in – and attempt to quantify – the “Morning Flight.” As in most years, it yielded a Connecticut Warbler (on 9/9), and on the 13th, a Lark Sparrow – my 184th species for me here, and the culmination of a record-shattering run at “my office.” Somehow, I didn’t have one in all of my time on Monhegan later that month, so this was a big score.

It was just about time for me to leave the store on September 16th to pick up my rental van for my WINGS tour to Monhegan that was starting the next day. Then the phone rang.

It was our friend, Barbara Carlson, visiting us from San Diego, who was out chasing the Little Egret at Gilsland Farm when she ran into Angus King, Jr, who asked her to identify a bird he just photographed. She called in excited panic as she attempting to explain to us, on Angus’s cell phone she borrowed, that there was a Mega-rare Fork-tailed Flycatcher there as well!

I pondered the timing, but somehow was wise enough to go pick up the van in Lisbon before driving to Falmouth. Notorious one-afternoon wonders, I was happy the Fork-tailed (my 377th Maine state bird) stuck around long enough for me to do the right thing first and not jeopardize my tour!

Joking about wanting to “see the Little Egret and a Fork-tailed Flycatcher from the same spot,” I turned around to scan the Presumpscot River and spotted two Caspian Terns! A species I see every year, usually just by normally birding the right places at the right time – like Biddeford Pool – this species had somehow eluded me all year. In fact, it was getting to be a bit of a year-bird nemesis, and I even resorted to unsuccessfully chasing one that was lingering at Hill’s Beach. I had all but given up on this species before this lucky sighting.

Even better, the flycatcher continued the next day to get my tour off on the right foot.

I departed for Monhegan for my second time this year on 9/17, with my WINGS tour for the next 7 days. With my year list sitting at 293, I needed my two fall tours to the island to come up big for me.

I missed my 4th Say’s Phoebe ever out here – one of my two biggest nemeses for the state! – this time by all of about 45 minutes! I did, however, luck into a Red-headed Woodpecker on the last day of its stay.

I only had Clay-colored Sparrows at non-sites up until this point, so that filled in a gaping hole, and a long-staying Yellow-crowned Night-Heron was a needed addition to the year list as well; none were found at Biddeford Pool this fall.

But overall, the slowest week I have ever experienced on Monhegan set me back in my quest – I simply needed more from my time there.

I was back on Monhegan the next weekend, with my annual Monhegan Fall Migration Weekend tour with my store’s group, and while I didn’t add much to the year list, I did get a big one: the first state record Cassin’s Vireo (For a more complete story, visit my blog entry from the weekend!)

Back on the mainland, I had some work to do. One last-ditch effort for Buff-breasted Sandpiper took us to Fryeburg Harbor (Site O3) on 10/3 on our way to a gluttony-fest at the Fryeburg Fair. Not surprisingly given the date, we didn’t find any “grass-pipers,” but we did find this Greater White-fronted Goose!

Jeannette and I took advantage of the flood tide on October 10th to hit the Eastern Road Trail to try to add Long-billed Dowitcher to my Big Year tally.

Every few summers, a Seaside Sparrows stakes out a territory in Scarborough Marsh, but this was not one of those summers. Therefore, I was quite happy when we found one here on this very late date. This was another stroke of luck, and my 299th species of 2017.

This was the type of strategizing that I really enjoyed throughout the year. Find a species that I “needed,” and figure out how to see it. Long-billed Dowitchers are rare-but-regular in Maine, and usually juveniles near the tail end of shorebird migration. The first full moon in October is usually a good time to see one out in the marsh, with areas of dry ground for roosting at a premium. And sure enough, there one was – my 300th species of the year!

November “Rarity Season” featured an impressive wave of southern vagrants deposited by a storm at the very end of October. I found another Hooded Warbler at Bailey Island, one at Fort Foster (Site Y1), numerous possible “reverse migrants” like very late warblers and Indigo Buntings, and more. But by having had good southerly luck so far this year, I didn’t add anything to my year list, until November 12th when I found a spiffy Yellow-throated Warbler at the most-unexpected location of Martin’s Point Park in Sabattus during my Birds on Tap – Roadtrip: “Fall Ducks and Draughts”. Being teased by a “flock” of three on Monhegan earlier in the month, and saving me from chasing a few later in the month, this was the type of serendipitous discovery that makes for Big Year fun, and proves the idea that the most important part of finding rarities is just being out in the field.

My only other Rarity Season “discovery” was finding an error in my checklist that showed me my count was one more (I call those “accounting errors”) than what I thought it was, so when, after much effort of searching, Jeannette and I found a Yellow-breasted Chat at Battery Steele on Peak’s Island (Site C11) on November 27th, I was now up to 303 for the year! It was also a very satisfying find, as this was one of the birds that I was putting a lot of effort into turning up. Again, this type of strategy of searching for specific birds in specific habitats at specific times of the year is much more productive, and fulfilling, than waiting for someone else to find something and racing around looking for it. Chats are notoriously hard to re-find in the fall, as they are ultra-skulkers, so self-found is even more rewarding – and much less frustrating!

The year was winding down, and few regularly-occuring species were likely anymore – regardless of effort. One bird that is likely much more regular than records suggest is Eastern Screech-Owl. I have found them more often than I have not when making concerted effort in southern York County, especially in winter. While I was unable to relocate one found in mid-November in York, I decided to make a dedicated effort come December.

On December 3rd, Pat Moynahan set out for an evening of owling in Wells. After a dusk-watch for Short-eared and Snowy Owls, I decided to try a little fishing for screech-owls. At the first stop we made, just after dusk, a short whistle resulted in not one, but two, very aggressive and vociferous Eastern Screech-Owls right over our heads (at an undisclosed location within Y5). That was too easy!

Luckily, the Greater Yarmouth Goose Fields (Site C15) finally yielded a rarity for me this year (other than an early-season Snow Goose which I also saw in the spring), with a Cackling Goose on December 6th for my 305th bird of the year in Maine.

In the world of retail, there’s not a lot of free time in December, and with this year’s snowy and icy weather, I had even less time to bird than usual. While I did find a bunch of good birds, like a total of 5-6 Snowy Owls (at least 3 not previously reported), an Orange-crowned Warbler along Eldridge Road in Wells (Site Y5) during the York County Christmas Bird Count, various lingering stuff like late dabblers, and half-hardies such as several Gray Catbirds.

I just had to suffer through enjoying winter visitors such as Snowy Owls, like this photogenic individual at Biddeford Pool on Dec 18th

As December waned, so did my chances for adding any new species. I was hopeful for a rarity to be discovered on one of the state’s Christmas Bird Counts, and while a few birds of note were turned up, nothing I “needed” was detected. We checked Marginal Way (Site Y4) in Ogunquit on the way home from a long Christmas weekend in Massachusetts, just in case a storm-tossed Thick-billed Murre was around. But while in Massachusetts, we did discover a Ross’s Goose on Christmas Day!

Now is where I would like to tell you I finished my Big Year with a bang; how I trudged through the snow and ice, braving sub-zero temperatures, marching up hill (both ways!), and digging out every possible addition for my year list. But alas, it ended more like a thud than a bang: a very snowy, very icy, and very bitterly cold thud.

Few birders were out to find something I might need, and it was even tough for me to motivate in the mornings with temperatures often below zero. But one of the aspects of a Big Year that I – and most every other participant in such a silly pursuit – enjoy is that extra little bit of motivation to get into the field.

Such additional incentive was more than necessary on December 27th and 28th, with morning lows of -5 and -10F, respectively. Without the hopes and dreams of one or two more species for the Big Year, it’s unlikely I would have done much more than sit around, watching the feeders and sipping coffee (and probably swearing at the cable news). Instead, I forced myself to get out for just a little bit, and while no year birds resulted, I did have some nice consolation prizes: two drake Barrow’s Goldeneyes were in the open water off of the Freeport Town Wharf (Site C19) on the 27th. And on the 28th, I had 2 adult Glaucous Gulls and two 1st-winter Iceland Gulls at the Bath Landfill (Site SA5). Then I sipped some coffee in front of the store’s windows (Site C19), hoping for a Common Redpoll to show up! That hour I spend in the evening in a last-ditch effort to find a Long-eared Owl in sub-zero temperatures was just stupid, however.

Besides, I wasn’t going to escape the cold the following day, when Jeannette and I (joined by Zane Baker) spent the entire day walking outside (low of -16, high of merely 6!) on the Freeport-Brunswick CBC. While Florida Lake Park is a site in our circle, our highlights were all away from there, led by the rediscovery of “our” Dickcissel (by plumage and proximity) at a feeder, about a mile from our store that he frequented from November 2nd through December 15th. He did not look happy about the temperature, either.

Winslow Park (C19) was the destination for our Saturday Morning Birdwalk on 12/30, and although the start temperature was a painful -11F, seven people showed up and joined me in enjoying a dashing drake Barrow’s Goldeneye

That left New Year’s Eve Day, and despite morning lows again well below zero, Pat Moynahan and I hit the coast from The Nubble (Site Y3) to Webhannet Marsh (Site Y6), with Thick-billed Murre primarily on our minds. Sea-smoke reduced visibility, and the wind chill was brutal. While we did have a total of 72 Harlequin Ducks – which certainly made us happy – our highlights were all from an extremely productive (and for the first time all day, mostly sheltered) Marginal Way in Ogunquit (Site Y4): 1 Fox Sparrow, 10 Lesser and 4 Greater Scaup, a Yellow-rumped Warbler, 3 Northern Pintails, and this very chilled Yellow-bellied Sapsucker that was eeking out a living on Eastern Redcedar berries. But alas, no murres – or shockingly, alcids of any variety.

Therefore, my 2018 Birdwatching in Maine: The Big Year finished at 305 species. When I started the year, my goal was 300, so I am quite satisfied with the tally. Additionally, I saw four species away from sites: Buff-breasted Sandpiper, Great Gray Owl, Bullock’s Oriole, and this Fieldfare – a first state record in a yard in Newcastle in April – for a total year list of 309.

The Great Gray Owl stings a bit, considering I missed one at a site (Sunkahaze NWR; Site PE9) in January while we were on vacation, and another showed up near the Orono Bog (Site PE7) in February. But it’s OK, it’s a Great Gray Owl, and site or otherwise, it was awesome.

Worse, however, was the Buff-breasted Sandpiper. Mayall Road in Gray/New Gloucester was one of the last sites cut from the book, and for some reason it was the only place I encountered one this fall. I even made concerted efforts to find them at likely places, such as the Colonial Acres Sod Farm in Gorham (Site C13). I guess I should have sucked it up and chased the three that were found there in September, or any of the handful of others that were found at various sites throughout the month.

Speaking of misses, as with any birding year – big or otherwise – there were plenty of misses. The worst might have been the elusive (usually) Least Bittern. After just about everyone (including most of my tour group), except I, saw the one that was on Monhegan over Memorial Day weekend, I never found time to make the effort to search for one in breeding marshes over the summer. That effort could have also yielded Common Gallinule, another miss for me in 2017, although the only reports of the year came from a non-site.

I always hope for kites and Golden Eagle at the Bradbury Mountain Spring Hawkwatch, but none passed through this year. There were a couple of Golden reports this fall though at sites, including one nicely photographed over Fryeburg Harbor. I also missed a Blue-winged Warbler on Monhegan this fall, as well as a Painted Bunting that left the day before my first tour arrived, while a Western Kingbird finally showed up there two days after I departed. I also dipped on a Franklin’s Gull that was a one-afternoon wonder at Wharton Point (Site C21) on 11/6.

Several other species were seen at sites covered in the book throughout the course of the year that I did not – or could not – chase. These included: Ross’s and Barnacle Geese in Aroostook County in October (Site AR7), Eurasian Wigeon at Messalonskee Lake (Site KE6) on 4/12, a Western Grebe reported off Sears Island (Site WO10) in January, Marbled Godwit at Reid State Park on 6/13, Sabine’s Gull off Eastport in September, a surprising Black-headed Gull at Riverbank Park (Site C12) a one-day wonder in February, and a Franklin’s Gull that flew by Dyer Point (Site C3) on 7/5. Surprisingly, the only Forster’s Tern reported this year was as out-of-place and unseasonable one at Sanford Lagoons (Site Y10) in April, while Royal Terns were briefly spotted at Popham Beach SP (Site SA2) on 7/16 and the Wells Reserve at Laudholm (Site Y7) on 8/19. I also missed Prothonatory Warblers at Wilson’s Cove Preserve (Site C22) on 5/2, and another on Monhegan on 5/16. A Cerulean Warbler was also on Monhegan on 5/21 – a species I have still not yet seen in Maine.

Off-limits but viewable via several boat trips covered in the book, Seal Island NWR hosted its usual slew of incredible rarities this year as well, including a Kentucky Warbler in May, a completely unexpected Gray-tailed Tattler in August, and several sightings of Long-tailed Jaeger in August. Whether or not you count Machias Seal Island as being “Maine” or not, it did host a Bridled Tern and an Ancient Murrelet early this summer,

My lack of an overnight birding-by-schooner tour to Seal Island cost me Leach’s Storm-Petrel for the year as I didn’t luck into any during my summer and fall pelagic trips. Of course, if I didn’t have a total of 4 Bar Harbor Whale Watch Company (Site H7) tours weathered out this fall, I might have picked one up, along with South Polar and Great Skuas – Great Skua remains my all-time nemesis in Maine waters!

And despite concerted effort in late December, I did not see a Thick-billed Murre this year. And Common Redpolls never did return by year’s end, after only a few made it to extreme northern Maine in the previous winter.

However, my most frustrating miss of the year might have been Brown Pelican. What was likely one bird was ranging up and down the coast, perhaps between Prout’s Neck and Plum Island, MA. But between June 9th and 12th, it was reliable off of Pine Point. I was Downeast with my WINGS tour. Until the last report on or about August 2nd, several birders lucked into it here and there, and several non-birders had sightings they reported: one friend saw it while taking a walk at the Camp Ellis jetty, and my landlord texted me a phone photo of it flying past Long Sands Beach (Site Y3) in York while he was out surfing. Oh well, it at least gave me something to look for during the summer, and I definitely spent a few days worth of time trying to turn it up at various coastal locales.

Additional species reported in Maine throughout the year that were not seen at sites covered in Birdwatching in Maine included Redhead (although it probably bred once again somewhere in Aroostook County, including at sites such as Lake Josephine), White-winged Dove, Scissor-tailed Flycatcher, Vermillion Flycatcher (first state record), and a couple of Western Tanagers.

So overall, I think I did quite well! While I am sure I missed a few things here and there, it’s safe to say I saw a large majority of the +/- 343 species observed in Maine this year, or roughly 89%, at sites covered within Birdwatching in Maine: A Site Guide.

I don’t use eBird, so my list “doesn’t count” according to some, but I took a look at the eBird Year List for 2017. My list was good for second in the state, despite my self-imposed limitations, quite a bit of travel (a total of 35 days out of the state this year), an exceptionally busy schedule all year, not to mention my aversion towards chasing more than the occasional mega rarity. I also visited 105 of the 201 sites covered in the book. Not bad. More importantly, it proved my hypotheses correct:

1) Birdwatching in Maine: A Site Guide has comprehensive coverage of just about every regularly-occurring bird in the state.

2) Using the guide to “just go birding” can result in a very respectable list, with just a little extra effort.

3) Birding in Maine is really special.

4) And perhaps most importantly for me: I would never do a Big Year for real!

Of course, I couldn’t have done this without my favorite birding buddy, Jeannette. In addition to having the year list pursuit occupy many of our days off together, she occasionally had to put in a few extra hours at the store here and there as I went gallivanting around the state. I also want to thank my friends who kept me company and helped me find birds, or otherwise assisted on my quest, throughout the year. I could not have accomplished this goal without the help of Zane Baker, Chris Bartlett, Kirk Betts, Paul Doiron, Terez Fraser, Kristen Lindquist, John Lorenc, Rich MacDonald, Phil McCormack, Pat Moynahan, Dan Nickerson, Evan Obercian, Luke Seitz, and Marion Sprague, and of course, all of the other contributors to the book who helped guide me way to numerous birding sites around the state. And I cannot forget to mention all of the other birders who found some good birds to twitch over the course of this productive year of birding in Maine.

As the calendar changed to 2018, like a many a real Big Year birder, I took a deep breath, relished the freedom of not being a slave to the list, grabbed my binoculars, and just went birding!

I hope you will do the same in 2018, and I hope Birdwatching in Maine will guide you along the way to a happy and successful year of birding, whatever goals you do or do not have. (You can order it directly from us at this link if you don’t already have a well-worn copy!)

Good birding, and Happy New Year List! If you keep one that it is (I won’t be!).

Common Nighthawk, Monhegan in May.

Hooded Warbler on Bailey Island in November, my 4th self-found HOWA of the year!